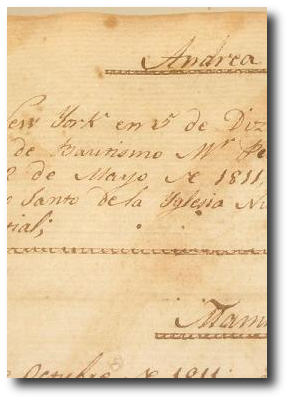

Dave HoingJune 2008 The Hand of the Dead But what of those faceless names in birth certificates and antiquarian bibles, employee lists and tax roles? Who is left to tell their stories, sing their songs, note their passing? I would do it if I could. The entries are written in Spanish, proud, feminine strokes sandwiched between the Apocrypha and the Gospel of St. Matthew. The bible itself is a recent acquisition, rare Americana from 1792. Each entry begins with a name. Andrea Francisca Nacio en New York en 25 de Diciembre 1808 This little daughter of unknown parents, born on Christmas Day in 1808, is the first of eight children listed; the last in this generation is Maria Veidra, November 12, 1831: twenty-three years of childbirth preserved in a sacred ledger. The entries continue but the hand falters, Spanish gives way to English, the proud strokes become more uncertain, sexless. In 1854 Maria marries a man named Francisco. The ceremony is held in her mother’s house and officiated by the Reverend Mr. Smith of St. George’s church. A child of this union, Elizabeth Andrea, ensues on October 8, 1855. And then there are no more entries; after nearly half a century, the story of a family mysteriously ends, with no hand to record the inevitable. Who came before Andrea, or after Elizabeth? I close the bible, stack it on top of Muratori’s Rerum Italicarum Scriptores. Books are meant to be stored in this manner: not upright but flat, safe from the ravages of gravity. I collect books for the same reason many people do, to connect with the past, to wonder about those who have held what I hold, seen what I see, thought what I think: as if the spirit of the dead could reach through the ages and touch my sense of awe. I consider this luxury of names I have stumbled upon. Andrea struggled into the world a scant six weeks before the birth, in Kentucky, of Abraham Lincoln; but had chance dealt some other hand, the two of them could have met. They could, in fact, have married. Perhaps it’s Andrea who gasps in horror at Ford’s Theatre as the assassin’s bullet shatters her husband’s skull and a nation’s triumph. Perhaps it’s their son Robert—Roberto?—who must replay this scene twice more in his lifetime, with Garfield, with McKinley. Or everything could have been different. What if, for instance, Andrea doesn’t like plays? Johnson never has to assume the Presidency, nor face impeachment: just another forgotten VP. Maybe Grant and Hayes still follow, maybe not. A very young Garfield may step onto the stage early, avoiding the wound he would have survived anyway had medicine then been as it is now. Or perhaps Andrea is disinclined toward politics altogether, and she and Abe set up a home in rural Illinois or New York, where he practices law and she tends a garden. The Civil War is managed by a less committed man, and the South wins. There are now two countries where there was once one. Southern blacks remain slaves. England favors the Confederacy for her cotton, which eventually leads to another war. I rub my temples: so many possibilities . . . No. Not possibilities, just what-ifs. The past is fixed. It doesn’t allow for alternatives. Andrea and her line stop with Elizabeth, disappearing into a backwater of history which stagnates with names and events that do not matter and insists the world remain what it’s always been. But what force drives the choices? What force decides that Abraham Lincoln will be born who he is, when he is, so he can be where he’s needed at the precise moment of crisis? What decree keeps two people a half a continent apart, drowning one in (perhaps happy) obscurity, while bathing the other in tragic glory? We hold human life sacred, we make speeches and deliver sermons, we teach our young to find meaning in their lives, and we believe that love will outlast time. And yet the vast majority of humankind is weightless flotsam, bobbing on the surface of history for a few years until, desiccated, they drift away to brackish oblivion, failing in any measurable way to have registered their existence. They bear children who bob and drift, their children bear children who bob and drift, and so on down the generations, people who do the best they can and then, through no fault of their own, are simply lost. Lost. It’s as if there’s only so much gravity to go around, and those who are called great get it all. But what of those faceless names in birth certificates and antiquarian bibles, employee lists and tax roles? Who is left to tell their stories, sing their songs, note their passing? I would do it if I could. I would walk back to New York in 1808 and find Andrea’s mother and I would tell her, I will remember you. I would introduce Andrea to Abraham Lincoln, as though it were possible for the weightless and the weighty to strike a balance. Then I would walk to 1855 and witness the birth of Elizabeth. I would watch her grow, and I would follow her where she goes, steering her away from those algaed backwaters, refusing to allow her to become becalmed in time. I would say to her, Learn to sketch and paint, write novels, scratch your name in the cornerstones of buildings; cry up to the heavens, I am here! Don’t get lost, Elizabeth. And if she smiled at me then, she would not get lost, for I would take her smile with me into the future. The world has turned since 1855, like numbers on an odometer. Everyone who was alive then is now dead; the great, the forgotten, and the never-knowns. They are gone, and I am not. And that is the difference, for I have been to the past, by way of elegant strokes entered into an old bible by the hand of the dead, and I will keep my promise to Andrea’s mother. I will remember. Tip the AuthorIf you liked this, tip the author! We split donations, with 60% going to the author and 40% to us to keep the flashes coming. (For Classic Flashes, it all goes to support Flash Fiction Online.) Payments are through PayPal, and you can use a credit card or your PayPal account. About the AuthorDave Hoing

Dave Hoing lives in Waterloo, Iowa. He works at a university library by day, collects antiquarian books by night, and fits in freelance writing when he can. In 2010, he and co-author Roger Hileman published a historical novel called Hammon Falls. It’s set primarily in Iowa between 1910-1940, with spatial stopovers in Paris, Dublin, Chicago, and Buffalo, plus occasional temporal side trips into present day. Your Commentscomments powered by DisqusCopyrightCopyright © 2008, Dave Hoing. All Rights Reserved. |